Learn how SAMBO (self-defense without weapons) was created in the Soviet Union, who the founders were (Oshchepkov, Spiridonov, Kharlampiyev), how Combat Sambo developed, and why it’s effective for street fighting.

Introduction — What is Sambo?

Sambo (from the Russian acronym SAMozashchita Bez Oruzhiya, “self-defense without weapons”) is a Soviet-era martial art and combat sport that blends wrestling, judo, jujutsu, folk wrestling and practical self-defense techniques. It began as a hand-to-hand combat system for the military and police in the 1920s–1930s and later split into the sport form (Sambo) and the military/combat form (Combat Sambo)

Origins — how Sambo got started

After the Russian Revolution and during the 1920s, the Soviet government sought an effective system of unarmed combat for soldiers and internal security forces. Coaches and researchers collected, tested, and synthesized practical techniques from Japanese judo, indigenous folk wrestling styles across the USSR, boxing, and other close-combat systems. That practical, eclectic mixing is what became Sambo. The name itself—SAMozashchita Bez Oruzhiya—literally points to the system’s purpose: self-defense without weapons.

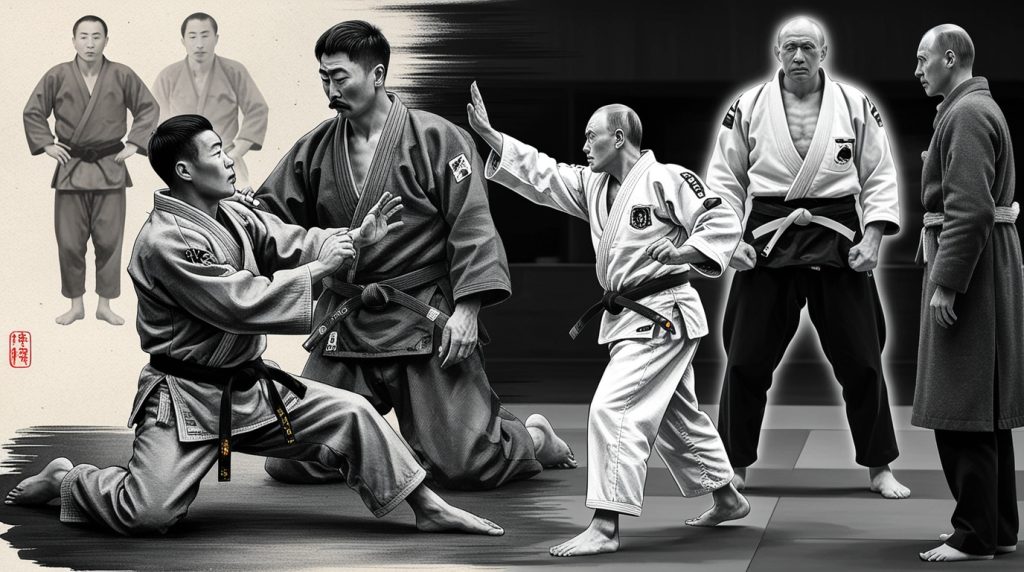

The main founders — Oshchepkov, Spiridonov, and Kharlampiyev

Sambo didn’t spring from one person alone. Three figures are central to Sambo’s origin story:

- Vasili (Vasiliy) Oshchepkov (1893–1937) — trained at the Kodokan under Jigoro Kano in Japan and brought judo knowledge back to Russia; he is credited with integrating judo techniques into early Soviet hand-to-hand systems. Oshchepkov is widely recognized as one of Sambo’s founding fathers.

- Viktor (Victor) Spiridonov (1882–1944) — a Russian military instructor and wrestler who developed a complementary, often gentler, system that emphasized techniques suited to wounded or less-athletic practitioners; he taught at Dynamo and worked widely to systematize self-defense methods.

- Anatoly Kharlampiyev (1906–1979) — a researcher and coach who collected regional wrestling methods and formally presented “Sambo” to Soviet sport authorities; Kharlampiyev is often credited with consolidating and popularizing the system and getting official sport recognition in the late 1930s.

These three names frequently appear together in authoritative histories and memorials as the key figures who created and propagated what became known as Sambo.

A turbulent history (short note)

Political turmoil shaped Sambo’s early history: Oshchepkov—who had close ties to Japan through his Kodokan training—was arrested during the Stalinist purges and died in prison in 1937; later research and posthumous rehabilitation corrected elements of the early record, while Kharlampiyev pushed Sambo into the official sports system

Sport Sambo vs Combat Sambo — how they differ and why Combat Sambo exists

- Sport Sambo (Sambo wrestling) focuses on throws, pins, and submissions within a ruleset similar to wrestling/judo; it’s practiced as a competitive sport.

- Combat Sambo was developed for military and law-enforcement use: it includes striking (punches, kicks, elbows, knees), throws, submissions, and defenses against weapons — designed for real-world, no-rules confrontation rather than sport scoring. Combat Sambo closely resembles modern mixed-martial approaches for military combatives.

Why Combat Sambo is effective for street fighting

1.Practical emphasis — Combat Sambo trains both striking and grappling in realistic sequences, so a practitioner is prepared for standing strikes, clinch work, takedowns, and ground control.

2.Simplicity & aggression — techniques are chosen for speed, efficiency, and damage (targeting vulnerable areas), not for aesthetics or tradition—this makes the system functional under stress.

3.Weapon defense & situational drills — Combat Sambo historically included training for police and soldiers on weapon retention, disarms, and improvised-weapon use, which is directly applicable in violent street encounters.

Legacy and modern status

Sambo is now an international sport governed by organizations like FIAS; Combat Sambo remains a respected military/police combatives system and has also influenced modern MMA and reality-based self-defense training. Its combination of throws, submissions, and strikes makes it uniquely versatile among stand-alone national martial arts.

Conclusion

Sambo’s story is one of pragmatic synthesis: teachers who studied judo and folk wrestling, coaches who systematized techniques for soldiers and police, and researchers who turned those techniques into a reproducible sport and combatives curriculum. From Oshchepkov and Spiridonov’s early experiments to Kharlampiyev’s formalization and the later development of Combat Sambo, the art remains valuable today because it was born out of real-world needs — not ceremony. If you train Sambo (especially Combat Sambo), you’re learning a discipline forged for survival and practicality.